What is Portosystemic (liver) Shunts?

A portosystemic (liver) shunt is a blood vessel anomaly that results in blood from the abdominal organs (small bowel, large bowel, stomach, etc.) being diverted to the heart and bypassing the liver. The condition may be either a birth defect – a congenital portosystemic shunt or may be acquired – commonly associated with chronic disease of the liver such as cirrhosis (scarring of the liver). This results in a liver that is too small, but also a build-up of toxins within the blood which can eventually damage your pet’s brain

Clinical Signs

In congenital cases clinical signs are often seen at a young age and include.

- Small stature

- Poor muscle development

- Behavioural abnormalities (walking around in circles, disorientation, unresponsiveness, a quiet demeanour, staring into space, pressing of the head against surfaces)

- Seizures

Other less common signs include

- Excessive drinking or urinating

- Apparent blindness

- Diarrhoea and vomiting

- Bladder stones

What investigation and treatment is available?

You will have a consultation with either an internal medic or a surgeon. Both will be able to discuss the disease in more detail. Your pet will then have a full physical examination, blood tests to include measurement of bile acids and/or ammonia concentrations.

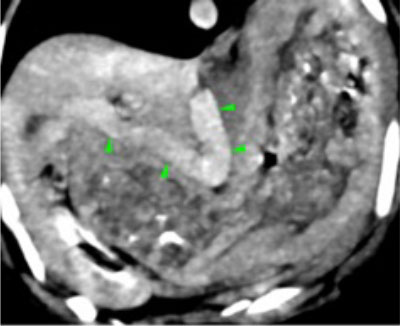

A liver shunt cannot however be definitively diagnosed by blood tests; shunting can only be found with advanced techniques such as ultrasound scans, specialised X-rays, CT scanning, MRI scanning, and/or exploratory surgery.

If a portosystemic shunt is diagnosed, surgery is rarely performed straight away, and medical management is usually used for at least one month in order to normalise your pet’s blood chemistry first.

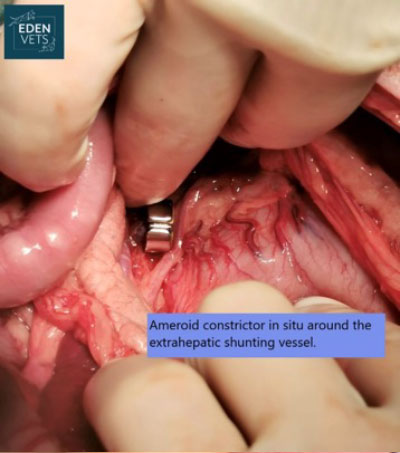

Surgery involves opening the abdominal cavity, locating the shunting vessel, and closing this vessel to re-direct its blood through the liver. In many cases, closure of the vessel must be carried out in a slow and gradual manner. This is generally achieved by the placement of a cellophane band or Ameroid constrictor around the vessel. Both cause a gradual closure of the shunting vessel over a four-to-six-week period. This gradual closure allows the previously under-used blood vessels within the liver time to develop without producing an excessively high blood pressure within the portal vein (portal hypertension).

Pets often remain hospitalised for a 3-5 day’s post-surgical treatment. They are nursed very closely in the postoperative period to monitor for signs of portal hypertension, hypoglycaemia, and seizure activity.

When patients go home, instructions are provided to restrict their exercise for the first week or so following surgery. They are routinely kept on medical management (restricted protein diet, lactulose syrup and possibly gut-active antibiotics) for up to six weeks following liver shunt surgery. If a patient remains without any clinical signs the administration of medications is reduced and subsequently stopped. We often repeat blood tests a few weeks after surgery to determine the success of the procedure.

What is the prognosis after surgery?

In many cases, the surgical management of a congenital liver shunt will result in the complete closure of the shunting vessel and the restoration of a normal blood flow to the patient’s liver. Such cases can be expected to lead a normal life, requiring no medication and with a normal life-expectancy. Cases with acquired shunts unfortunately have a poorer outlook, often requiring lifelong medications and monitoring